Exploration & Adventure

Our story begins at the foothills of eastern Himalaya, in a tightly packed landscape known as the “Chicken Neck of India’ where wild Asian elephants once roamed freely through dense forests and jungles, rich with nourishing food and water.

Out from the trees across the field rises a noise I have only heard in movies and dreams: the resounding trumpet of an elephant. From a patch of trees directly to our right, another elephant responds with an earth-shaking full bellow roar, accompanied by a steady and thunderous rumble that rattles me to my core.

Elephants, horses, camels, elephants, oxen, dogs, mules… From the dawn of time, humans and certain animals have developed a complex synergy, a reliance on one another that has, at its root, the meeting of both of our most basic needs: food and shelter. A delicate balance of co-existence—in many cases fraught with domination and cruelty, and in countless relationships an exchange of deep love and affection, often times both.

“Here is a story,” she had told us a few days before. It was raining then as well; monsoon season and the parks are closed to all but the forest patrol, mahouts, the elephants, and us. We sat on chairs along a wall that blocked any hope of a breeze, not daring to move. The heat was as thick as the jungle that spread out before us. Parbati in a grass green tunic and athletic sweats, rainbow flip flops and faded crimson painted, ridged nails. She took up half of the chair space; she may have been floating. I had waited a week for this.

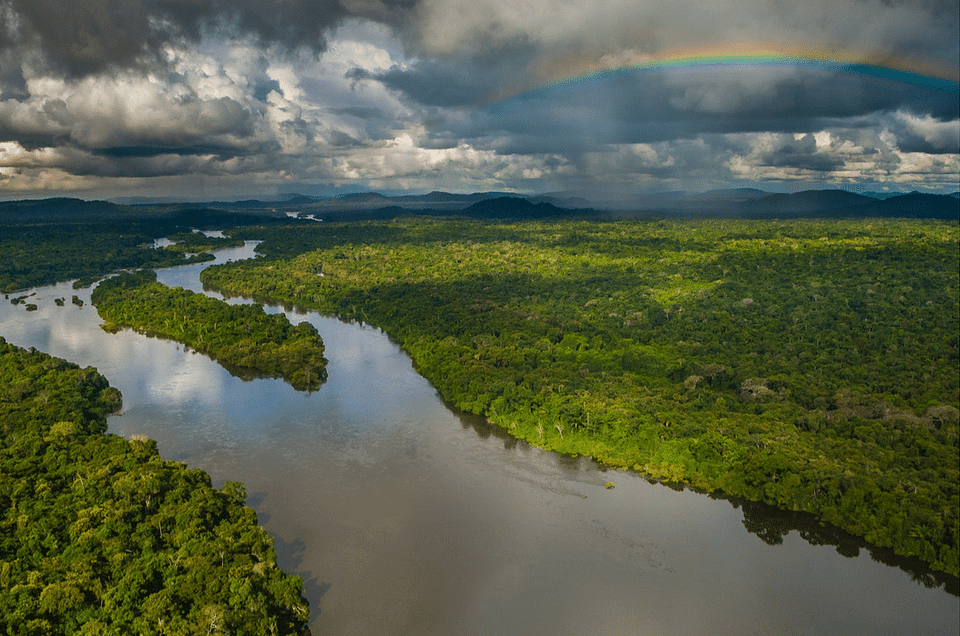

In a raw world that seems to bleed everyday with shriveling resources, human tragedy, and environmental ruin. Where every moment with a press of a button or a swipe of a screen, we are assaulted with distressing news, stories and images that threaten our sense of security and dim our lights, we must find ways to remain optimistic. We must work to remove the physical and metaphorical barriers that block our meaningful connection to one another and to our planet. In my 25 years documenting remote tribal communities around the world and have learned important lessons from their collective wisdom.

Fear and fascination are often two sides of the same mind, and in an internal standoff, one will ultimately prevail. Even as fear fights a robust battle within me, fascination almost always tends to win. I am driven to spend weeks and months in the most extreme places on earth—deep under the icy Antarctic seascape and alone in the vast swirling blizzards of the Arctic. I was born to do this. My mind, body, and soul are more at home here than anywhere else. Through the risks and challenges, my innate comfort on sea ice has become my strength, allowing me to open a window into the rarely-seen world of both polar regions.

Like all worthy quests, my fascination with Mongolia begins with a story. A story that turns itself like polished stone within my fingers. A tale I replayed so often since childhood, that when I close my eyes, the characters appear, fully defined, as if I could touch them. At the center is my grandfather. A young French soldier fighting in World War II. I see him then in black and white, even though when he sat me on his knee, decades later, to tell this story, he was colorful in every way imaginable. It is as if my grandfather had grown up through a period of time when everything existed only in shades of black and grey, as if the entire world with its violence and scarcity had the color sucked right out of it.

We’ve been waiting for snow for weeks so we can migrate to the winter camp where the reindeer herd will have enough food and Lena’s family can settle in with their new infant. However, snow has been slow to arrive and the baby’s birth is impending. As in all births, planning at this scale can be tricky.

The fire has gone out and the temperature has dipped to –20ЉC degrees inside our simple, but effective, shelter – the Nenets’ winter chum, built from layers of reindeer skin and fur and supported by larch-wood poles. Beyond the door flap, the landscape is flat and barren as far as the eye can see. The view is endless withered brown grass with pockets of berry bushes.

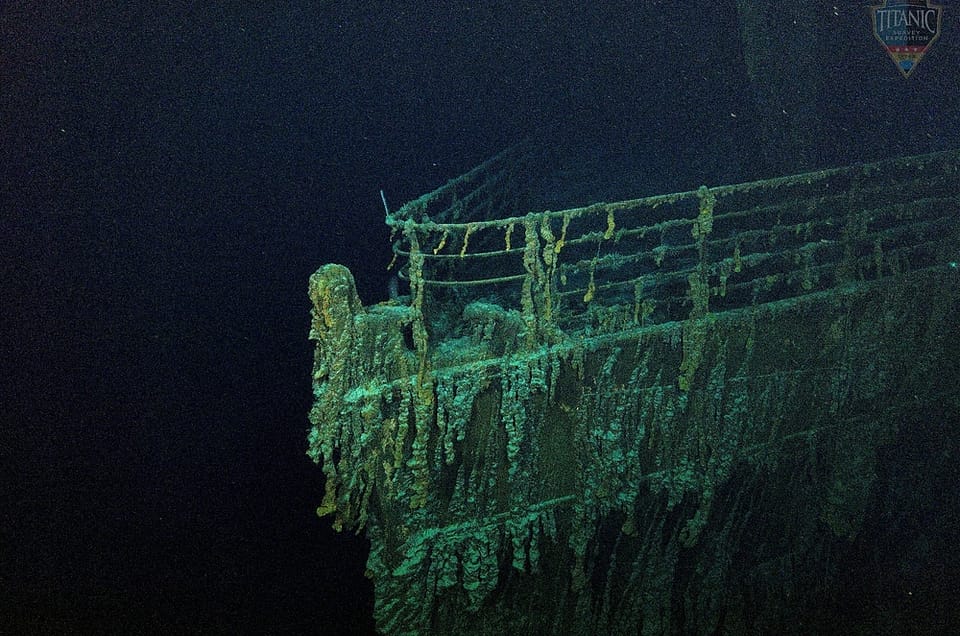

June 30, 2015: Time is running out. Day five of a weeklong expedition and the too-swift current still carries considerable risk. The Aegean Sea is a magical turquoise that inspires a vision of Neptune rising, but that tranquil scenery belies what is happening beneath us. Placement of our diving vessel, the UBoat Navigator, is crucial and we cheer as the mark we are waiting for appears on the sonar. We are directly above the wreck of the HMHS Britannic, Titanic’s sister ship, sunk by a German mine a century earlier.

Typically when you see Rebecca Rusch’s name attached to Red Bull Media House film you think: action adventure, drive to win, blood, sweat and tears. But wait, here is Rebecca holding up a black and white photo of her father next to his bomber plane, taken months before the plane went down, during the Vietnam War. She is showing the image to an unknown riding partner, Huyen Nguyen, a champion Vietnamese cyclist, whose father survived U.S. bombings in his neighborhood. In their garden a bomb hole still exists, now a pond for fish.

At the Sun Valley Road Rally’s No Speed Limit Open Road event. Driver Scott Riedl, with this writer in the passenger seat, pulled some serious Gs in “Insane Mode” to exceed Tesla’s top speed, reaching an unprecedented 157.9 mph and making electric car history.